From: John Conover <john@email.johncon.com>

Subject: Re: Exposing my ignorance

Date: Fri, 7 Aug 1998 15:13:02 -0700

John Conover writes:

>

> If, and only if, it is a fractal, then the range will go up with the

> square root of the day scale, and the standard deviation will remain

> constant. (Actually, to be mathematically precise, fractals are a

> whole family of such things-the range could go up on the n'th root of

> the time scale. If it is true Brownian motion-the most common type of

> fractal-it will be the square root, which is the hallmark signature of

> a random process, with independent increments, and a Gaussian, or

> Normal, distribution.)

>

> If we compute such a data set from empirical data, we would want to

> plot it on log-log paper, since the square root, (or n'th root,) would

> plot linear-with the slope of the graph equal to the root, n. This is

> called Hurst's rescaled range/scale analysis after the hydrologist

> H. E. Hurst who invented it in the 1950's. (If rain happens randomly,

> and we sum the rain into a reservoir, how high do we have to build the

> dam such that it doesn't overflow-that's the problem that Hurst was

> working on.) The slope of the graph is called Hurst's exponent.

>

Hurst's method is general, and can be used to analyze "chaotic," (ie.,

non-linear dynamical,) systems, also. There is mounting, although not

compelling, evidence that equity prices are chaotic phenomena. Chaotic

systems are an extension of fractal systems, and the two share many

common characteristics. A good way to think about it is that fractals

are a first order approximation to more complex systems, like those

that exhibit chaos.

The Stanford economist Brian Arthur has published a formal proof that

equity prices vacillate (formally, bifurcate,) between fair market

prices, and speculative escalation. Further, this vacillation will be

cyclical, indicating that the system is governed by what is called an

"attractor." The proof concludes that the attractor has fractal

characteristics, ie., it appears at all scales, or levels of

complexity-eg., it is an infinitely complex system-making the

attractor what is termed a "strange attractor." If this is true,

Hurst's method should lend some empirical insight into the phenomena.

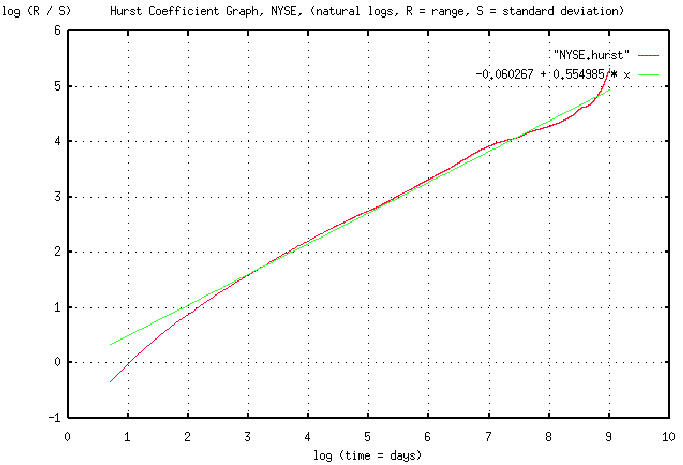

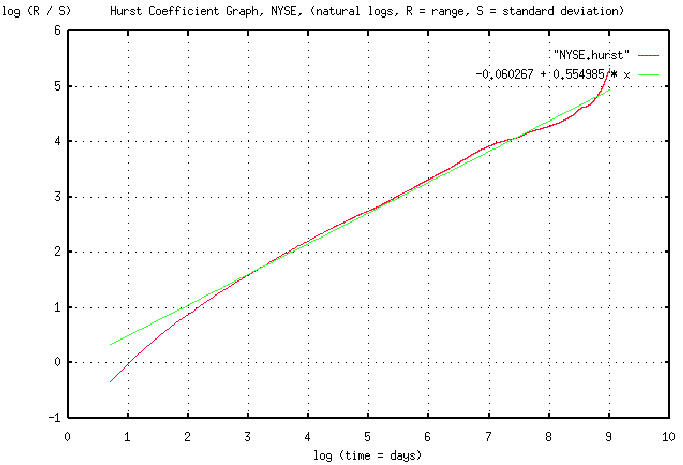

Such analysis requires enormous amounts of data. The attached is a

graph of the Hurst exponent for the daily New York Stock Exchange

Composite, inclusively between 3 January, 1966 and 30 July, 1998,

using the data from http://www.nyse.com/public/market/2c/2cix.htm. The

data for the graph was generated by the tshurst.c program, and took a

little over 13 hours to execute. Overlaying this graph is a least

squares linear approximation to the graph. The graph is in pdf format.

The "ripples" ie., the cyclic phenomena, of the strange attractor can

be seen as the difference between the two graphs. What this means is

that the NYSE is not entirely a random process-there are cyclic

correlations where the probability of prediction rises above 50% to

approximately 60%. And that is exploitable. The largest cycle occurs

at about 4.33 year, (log (1062) days = 7 on the graph-there are 253

trading days in a year,) intervals, (why, no one knows,) and one of

these cycles started at about early October, 1969. The implications

are:

1) Prediction based on near term data is very unreliable, with a

probability of success of 50%-near term being a year, or so.

2) To get an idea of what the market will do in the near future,

there is about a 60% chance that it will be repeating what it did

4.33 years ago. The reason for this is that where the Hurst

exponent (ie., the slope of the graph,) is 0.5, no predictability

exists-however, during the up-slope of the ripples, the graph

steepens, to about a 60% slope, meaning that a 60% predictability

exists. When the slope of the graph goes below 0.5, the situation

is anti-cyclical, (ie., there is a 60% chance that the market will

be doing the opposite of what it was doing.)

3) The ripples in the graph occur at all scales, but the change in

slope is less pronounced, meaning that the predictability

decreases below 60%.

John

-- John Conover, john@email.johncon.com, http://www.johncon.com/